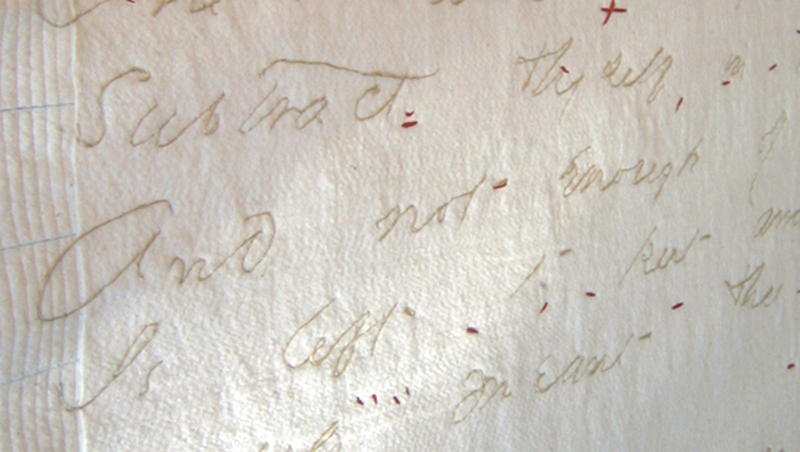

| actual fascicle, picture credit emily dickinson museum |

Jen Bervin embroiders Emily Dickinson’s handwritten

punctuation and editorial notes

I have to explain why I just fell in love with these images. I am a huge Emily Dickinson gruppy...before my father's and now my mother's illness I use to go to Amherst every summer. Go to her house, walk upon the creeping/creaking floor boards, try to find spells that might remind me of her, stand and meditate in her room, and finally sit in her garden...I've even wandered to her grave site. After visiting her house I'd walk over to her brother Austin's house...along that narrow path that she described as suitable for two lover to meet along...and get lost in that world. Lunch was had at an hold hippie joint called the Black Sheep! and a walk around the short turn to the historic society's museum. But now...just lots of memories I'll try to keep hold of until I'm back there one day. However, enough about me...Sunday's eye candy...this beautiful work...What a great idea. I copied but credited all the site that I got information from. Hope this is enjoyable and as good a read for you as it was for me.

Textile artist Jen Bervin has created something wholly peculiar and wonderful in her project The Dickinson Fascilies. During her lifetime Emily Dickinson tried to avoid publication, referring to it as “the auction of the mind,” and yet she continued to write, completing some 1,700 poems.

Between approximately 1858 and 1864, Dickinson grouped her poems into small handbound packets, later called fascicles. They are very humble bindings: stab-bound with twisted red and white thread and tied off teeteringly near the folded edge. The stitch held the stacked folded sheets together but made them a harder to open. [...] Her fascicles and fragments were dismembered, regrouped, scissored, and marked by her various editors as they changed hands and often her poems have been restructured and changed considerably for print.

Interested in the editorial patterns Bervin abstracted the editor’s notes, punctuation and other details from Dickinson’s poems and used cotton and silk thread to embroider the marks on enormous cotton sheets nearly 6′ tall by 8′ wide. I’m seriously geeking out over these. A fascinating idea. (via quipsologies)jen bervin embroidery from colossal (source for text and images)

Jen Bervin web page. if you want more http://www.jenbervin.com/html/dickinson.html

A series of six large scale embroidered works by Jen Bervin based on composites of the punctuation and variant markings in Emily Dickinson's poetry manuscripts.

A new edition on the series is available now from Granary Books:

Jen Bervin, The Dickinson Composites, Granary Books 2010

Unbound pages and sewn samples from the Dickinson Fascicles

Edition size: 50. Order here.

The Composite Marks of Fascicles 40, 16, 38, and 34. Sewn cotton batting backed with muslin. Each quilt is 6 ft h x 8 ft w.

Emily Dickinson avoided publication, calling it “the auction of the mind,” but penned nearly 1700 poems in her lifetime. Readers are familiar with her characteristic dashes, but fewer have seen her equally ubiquitous crosses (+ marks) or the variant words to which they correspond because they are rarely reflected in print editions.

The variant words are preceeded by the + mark and often appear listed in clusters after the poem but before the horizontal line Dickinson drew to signal the end of a poem. To read the variants, you move backwards through the poem trying to find the point of insertion, the corollary word or phrase (preceeded by a +) that the variants refer to in the poem. They are sometimes quite close in meaning to the marked word, but in other instances, they are as far ranging as "+ world, + selves + sun."

Between approximately 1858 and 1864, Dickinson grouped her poems into small handbound packets, later called fascicles. They are very humble bindings: stab-bound with twisted red and white thread and tied off teeteringly near the folded edge. The stitch held the stacked folded sheets together but made them a harder to open. The poems are composed on stationery typical of the nineteenth century, vertically folded sheets, plain, laid, or ruled paper with a small embossed image in the upper left corner. The packets contain eleven to twenty poems per grouping.

Detail. Jen Bervin, The Composite Marks of Fascicle 28.

In 1981, Harvard University Press issued a landmark two-volume facsimile edition of Dickinson’s handwritten manuscripts, edited by R. W. Franklin. The edition includes forty of Dickinson’s fascicles—stab-bound packets (non-nested sheets of folded paper) containing eleven to twenty poems per fascicle. The manuscripts also contain a number of unbound sets; her late fragments and letters have yet to be published in facsimile editions. Dickinson’s own publication of her poems is highly specified given that she enclosed poems and lines from poems within letters in correspondence, tuning them subtly for different recipients.

Dickinson’s editorial legacy is complicated at best; her fascicles and fragments were dismembered, regrouped, scissored, and marked by her various editors as they changed hands and often her poems have been restructured and changed considerably for print. Even the current variorum edition of Dickinson’s work persists in defying her line breaks and removes or replaces her crosses with other marks (brackets and numbers to clarify, i.e. change, the system that Dickinson authored). By imposing conventional views of literary authorship (as expressed by book publication) and divorcing her poems from their formal integrity and its intended specificity, the implications of an unusual, complex, pervasive system are harder to understand.

Jen Bervin, The Composite Marks of Fascicle 28. Cotton and silk thread on cotton batting backed with muslin. 6 ft h x 8 ft w.

I wanted to see what patterns formed when all of the marks in a single fascicle, Dickinson's grouping of poems, remained in position, isolated from the text, and were layered in one composite field of marks. The works I created were made proportionate to the scale of the original manuscripts but quite large—about 8' wide by 6' high—to convey the exact gesture of the individual marks. I scanned Dickinson’s manuscript facsimiles (about twenty pages per fascicle), edited them digitally to form composites of just the marks, and used a projector to transfer the marks onto cotton batting (to suggest a highly magnified page) prepared with a hand-sewn center line (a stand-in for the folio fold) and machine-sewn lines that replicated those of the light-ruled laid paper or blue-ruled paper. I embroidered Dickinson’s marks in with handspun hand-dyed red silk thread.

The fascicles from which I made composites showed clearly identifiable shifts in the size, gesture, frequency, and distribution of the marks. In contemplating such an odd physical study, one naturally forms one’s own questions about the nature and meaning of the marks; it makes their presence on the facsimile manuscript page more striking, systemic, factual—and their omission from typeset poems more evident.

I have never doubted Dickinson’s profound precision, however private, nor that the energetic relation of these marks and variants is anything but integral to her poetics. I have come to feel that specificity of the + and – marks in relation to Dickinson’s work are aligned with a larger gesture that her poems make as they exit and exceed the known world. They go vast with her poems. They risk, double, displace, fragment, unfix, and gesture to the furthest beyond—to loss, to the infinite, to “exstasy,” to extremity.

The Composite Marks of Fascicle 34. 6 feet high x 8 feet wide. Cotton and silk thread on cotton batting backed with muslin.

The Composite Marks of Fascicle 38. 6 feet high x 8 feet wide. Cotton and silk thread on cotton batting backed with muslin.

The Composite Marks of Fascicle 19. 6 feet high x 8 feet wide. Cotton and silk thread on cotton batting backed with muslin.

Detail, The Composite Marks of Fascicle 19.

The Composite Marks of Fascicle 16. 6 feet high x 8 feet wide. Cotton and silk thread on cotton batting backed with muslin.

Fascicle sixteen contains the first insert page, a smaller sheet pinned in with a straight pin. The hand-embroidered black text is taken from from this insert page and reads: And could I further / “no”? Emily Dickinson wrote in a letter to Judge Otis Lord, “And don’t you know that “no” is the wildest word we consign to language?"

.jpeg)

Emily Dickinson's fascicles bound with twisted red and white thread .... and Jen Bervin's embroidered art work ..... I find this all so intriguing. It must have been wonderful to wander about Emily's house and then to follow the path to her brother's house. Thanks so much for sharing.

ReplyDeleteWonderful! Thank you for the education. :-)

ReplyDeleteThis is fantastic. I did not know about Jen Bervin's work, and am thrilled to have discovered it thanks to you.

ReplyDeleteRoni Horn also works with Emily Dickinson's text - you probably know this, but I just read an article about her work, so it is fresh in my mind.

Wonderful to discover your blog.

Wish you'd been to the Homestead on Emily's 181st birthday a couple of weeks ago - we would have met. It was an amazing night and a great celebration. I run an Emily Dickinson Facebook page and will link to this blog right after our Christmas entries.

ReplyDeleteWe're very interested in the fascicles. I actually was allowed to HOLD Emily's original ms. poem "Alone and in a Circumstance" in my hand!

- Lenore Riegel